10 YEARS IN THE MET

“He came in a frost, turned on the heat and left in a blizzard of his own making!”

Tony Judge: Mark’s Capital

The frost that my father experienced as an outsider lasted for four years, until he became Commissioner. He described them as the worst four years of his life. He was ostracised by the others of his rank, and kept at a distance by the Commissioner. He and my mother were “sent to Coventry” at social gatherings, continually ignored and isolated at events that they were obliged to attend. However they did establish a few deep and enduring friendships, such as with the Receiver of Scotland Yard, Kenneth Parker, and his wife, Freda, the head of the Solicitors’ Office, Cappy Lane, and his wife, Nan, and the head of Public Relations, Bob Gregory, and his wife Ruth [whose wedding present of a beautiful Stilton dish still sits on my dresser today] – all people of discernment!

The frost began to thaw as my father began to make what changes he could to improve the working conditions of the men and to alter the disciplinary procedures so that policemen convicted of criminal offences were then given the sack and any detectives who were acquitted were returned to the uniform branch. These actions were met with great approval from the many officers who served with honesty and good intentions.

The frost melted when my father became Commissioner in 1972. He cleared the force of corruption, doubled the number of policewomen, instigated new structures for a more efficient administration of the entire organisation, challenged both political and legal systems and fought some very successful campaigns against terrorists. After the successful conclusion of the Spaghetti House siege, Sir Robert Thompson, a distinguished specialist in anti-terrorism, called him: “the best policeman in the world” and the conduct of the Metropolitan Police: “the envy of the world”.

The first time I truly realised that my father had become a public figure of significant standing was in November 1974, when I looked down at the Sunday papers, lying on the floor of the hall way in our house in Elaine Grove, and saw his face staring up at me from the cover of the Sunday Times. It was a superb portrait of him, taken by Lord Snowden. I read about him more than I saw him, because during the early seventies I was very preoccupied in bringing up my two young children, Rachel and Marcus, although I knew that he would always be there for me if I needed him, which indeed he always was, right up until the end of his life.

The heat intensified during the four years and nine months of my father’s time as Commissioner. He became a public figure of great authority, but one under increasingly great pressure – for example, there were regular death threats from the IRA, who tracked all his movements. The lives of his family were threatened as well but he told both them and the IRA that there would be no bargaining under any circumstances, because he felt that human life was of little importance when balanced against the principle that violence must not be allowed to succeed.

There is an address given by my father at the funeral of Captain Roger Goad, who was blown to pieces whilst bravely trying to defuse a bomb, in the chapter on Balcombe Street [p177] in “The Office of Constable”, which demonstrates most powerfully his response to all terrorist activity.

In 1977 my father was made a Freeman of the City of Westminster. I only discovered after his death that he was one of only six people to receive this honour, two others of whom were Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher. At the reception given to celebrate his award I remember one of his work colleagues saying : “I never realised that it could be so much fun working for Sir Robert!” He was very welcoming and friendly to everyone that he met, whatever their rank or social status. He related to what was real in a person, and was always willing to listen properly to people.

My father had a wonderful northern wit, dry, acute and highly perceptive, inherited from his Lancashire background. His legendary quote that: “the police should catch more criminals than it employs!” is a succinctly worded observation. He made another highly entertaining comment to a journalist who asked him what he would do if a politician, or even a cabinet minister was kidnapped, to which he replied: “I would send in some more!” All his family spoke with the wonderful directness and earthiness characterised by people who come from the north of England. When my grandmother, Louisa, saw a photograph of her youngest son in full “fig”, standing with the Queen, Prince Phillip, Princess Margaret, Lord Snowden, Princess Anne, the Duke and Duchess of Kent, Lord Mountbatten and various other dignatories, she commented: “That’s all very well, but when does he do his real work?”

The blizzards came when my father decided to retire. The impetus came through the Police Act 1976, which was introduced to bring an independent element in to the handling of complaints against the police, declaring that that the ultimate responsibility for police discipline would go to political nominees. My father felt that this act was detrimental to what he had achieved in preserving the independence of the police in disciplinary matters and indeed as a service in its own right.

My father also wanted to be in a position to start saving some money, so that he could build up some funds for his family. A Commissioner in the 1970s earned £18.675 a year, compared with a Commissioner in the 2010s, who earns over £1000.00 a year. My parents lived quite frugally – they did not have the income for any luxuries and most of my father’s income was spent on living expenses. My father was now in a position to take up offers to write, to give lectures, to research, to sit on Boards and to explore new challenges, such as developing the formation of the Australian Federal Police. Many new opportunities opened up for him, and he was ready to undertake them with the same enthusiasm, focus and diligence that he gave to his forty year’s career with the police.

My father also felt that his “inventive “ capacity was running out. He had completed all the changes that he had in mind when he took office. He worked at such a pace during those four years and nine months that the felt like he had run out of steam!

Finally, he believed that a period of five years was long enough for anyone sitting in the Commissioner’s seat, not only because of the intensity of the pressure of the work but also because of the insidious nature of the corruption of power, with its danger of complacency, the diminishing willingness to pay adequate attention to opposing points of view and the inevitable tendency to dwell on past events rather than to seek new challenges.

And so, for all these reasons, he believed that it was the right time for him to leave the Metropolitan Police.

0

0Speech – Bramshill College

0

0Speech – To conservative women

0

0Speech – Keeping the peace in GB

0

0Quest for a representative police force

0

0Notting Hill and the police – letters to the editor

0

0Notting Hill again

0

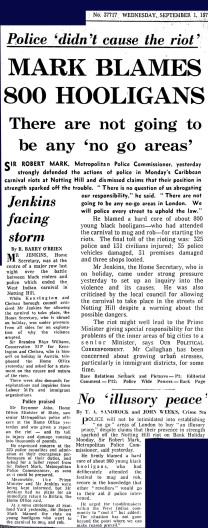

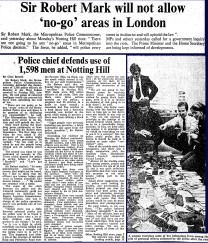

0No no-go areas

0

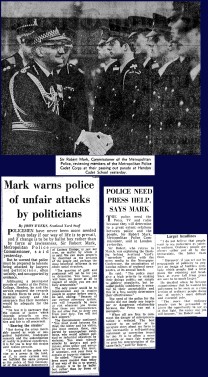

0Unfair attacks by politicians

0

0Ill-equipped to handle riots

0

0Carnival Riots